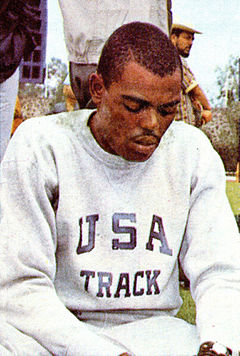

Willie Davenport

Sport: Track and Field

Induction Year: 1988

University: Southern

Induction Year: 1988

In the 1964 Olympic Trials, 19-year-old Willie Davenport of the United States Army upset five-time national AAU champion Hayes Jones and Blaine Lindgren in the 110-meter high hurdles.

At that time, the fastest hurdlers in America were the fastest hurdlers in the world. In the Olympic Games, United States hurdlers had scored 1-2-3 sweeps in four consecutive Olympiads.

It didn’t happen in 1964 because Davenport pulled a muscle two days before the competition got under way in Tokyo . After he was eliminated in the semifinals, Jones and Lindgren finish 1-2 in the finals and Anatoly Mikhailov of the Soviet Union got the bronze medal.

But if you’re thinking Davenport ‘s once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for an Olympic medal went down the drain, guess again.

He came back, again and again, in the next 12 years.

Davenport enrolled at Southern University in Baton Rouge after his discharge from the Army and was ranked No. 1 in the world six consecutive years. Rodney Miburn, another Southern University product, ended his streak in 1971, but Davenport came back five years later and was ranked No. 1 in the United States in 1976.

In the 1968 Mexico City Games, when Bob Beamon shattered the world record in the long jump and other black athletes were expelled form the Olympic village for making black power salutes on the victory stand, Davenport won the gold medal with an Olympic record clocking of 13.3 seconds.

He was so nervous before the race that he nearly fell down taking off his sweat pants. But from the starter’s gun, he recalled, “I knew I had won the race. It was perhaps the only race I ever ran that way, but that first step was so perfect—right on the money. I coasted over the last three hurdles thinking, ‘It’s over, it’s over.’”

It wasn’t over. He beat Milburn in the 1972 Olympic Trials. In the Munich Games, when Mark Spitz won seven gold medals in swimming and 11 Israeli athletes were taken hostage and murdered by terrorists, Davenport finished fourth.

In 1975, Davenport suffered a ruptured tendon in the national AAU meet at Eugene , Oregon . They told him that the necessary surgery could cause a limp. After the operation, a blood clot was found in his right knee.

One year later, Davenport returned to the same track for the Olympic Trails. “They carried me off on a stretcher,” he said. “I told them I’d be back. And here I am.”

In the 1976 Montreal Games, Davenport finished less than one-tenth of a second behind the winner. But he returned to the victory stand to accept the bronze medal, as Guy Drut of France finally ended a half-century of U.S. victories and Alejandro Casana Ramirez of Cuba was second.

It still wasn’t over. The United States didn’t participate in the 1980 Summer Olympics because of President Jimmy Carter’s boycott, but Davenport qualified for the Winter Olympics as a member of the U.S. bobsledding team.

Davenport took his bobsledding career seriously. The United States team finished 12th at Lake Placid, but Davenport proudly noted that “we set an American record.”

Before he finally called it quits in the hurdles, Davenport finished in the top three of the national AAU championships nine times, and was in the top six 11 times. Both of those are all-time records in the high hurdles, and his career total of four championships is only one behind Jones’ record five.

For the man they called “Old Bones,” it all started when he launched his hurdling career as a junior at Holland High in Warren , Ohio .

He started his junior season running the 100-yard dash, but was switched to the hurdles in the middle of the season and won the district title. The following year, he set a state record of 14.2 seconds—but that wasn’t fast enough to attract the attention of college talent scouts. Kent State offered him a partial scholarship, but Davenport enlisted in the Army and took paratroop training. After 20 jumps, he was sent to Germany —where his track career was revived.

The day he arrived at the new post, he saw a notice on the bulletin board inviting candidates for the track and field team to report. Taking the recruiting slogan (“Be the best that you can be in the Army”) seriously, he decided to give it another shot. A German coach was impressed with his performance, and Davenport competed for both the Army team and a local club while he was in Germany .

When he was discharged in 1965, he was ranked No. 1 in the world and had plenty of attention from college coaches. A couple of former Southern University athletes, Theron Lewis and George Anderson, convinced him to go to Southern, where Dr. Dick Hill had developed a national power.

Later, he felt his low-key approach to training may have been the key to the longevity of his career.

Davenport , who served as executive director of the Baton Rouge Mayor’s Council on youth Opportunity after hanging up the spikes, said the respect he gained from his peers made it all worthwhile.