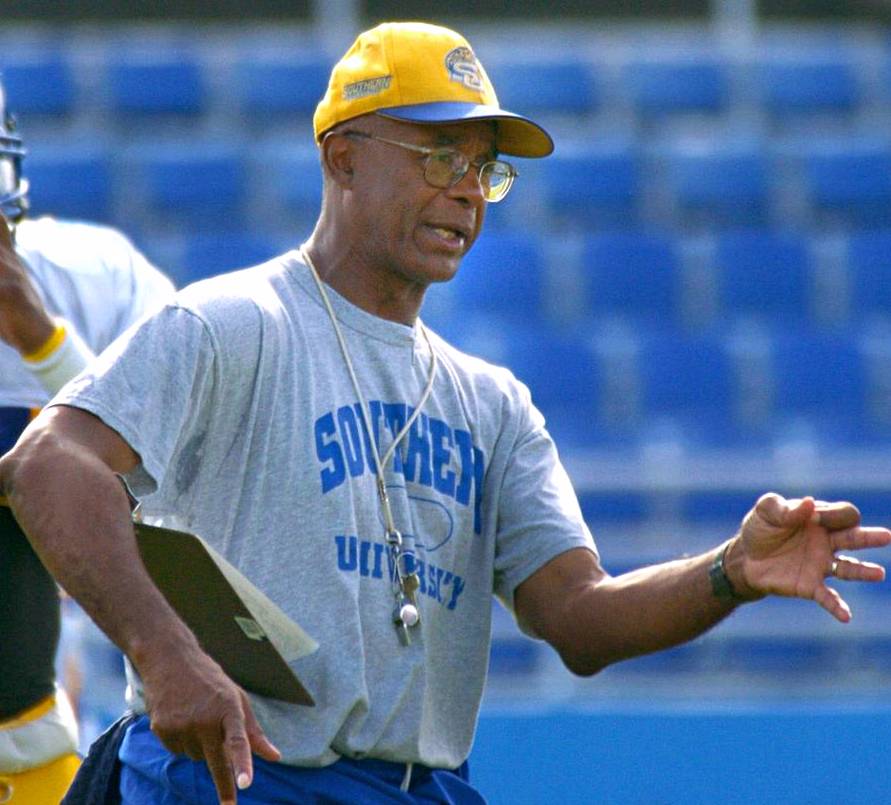

Pete Richardson

Sport: Coach

Induction Year: 2012

University: Southern

Induction Year: 2012

Pete Richardson defined Southern University football from his arrival in 1993 to 2009, establishing himself on par with the school’s other coaching legend — College Football Hall of Fame and Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame member A.W. Mumford. Richardson. He won five Southwestern Athletic Conference titles, including a three-peat from 1997-99 (the school’s first consecutive SWAC titles since 1959-60), four black college national titles (1993, 1995, 1997 and 2003) and four Heritage Bowl titles. Richardson is 12-5 in the Bayou Classic and is the only SWAC coach never to have lost to Eddie Robinson. His winning percentage of 68.4 percent in 17 seasons (134-62) at the school is second behind only Mumford’s 70.4 percent (176-60-14). Prior to his arrival, Southern had last won the SWAC in 1975 and 1966. The program had four different head coaches in the 1970s and four between 1981 and 1992. His impact was immediate, however, as he took over a program that had three straight losing seasons and guided it to an 11-1 record, winning the SWAC and black college national titles. At SU, Richardson had four 11-win seasons — including a 12-1 run in 2003. His career record, including five seasons at Division II Winston-Salem State, was 176-76-1. A seventh-round draft pick of the Buffalo Bills in 1968, he played defensive back from 1969-71. He had eight interceptions and five fumble recoveries in 39 career games. Born 10-7-45 in Dayton, Ohio.

By Perryn Keys

Baton Rouge Advocate

The teams always found a way to disappoint. Championships were a pipe dream. And the end of every season came with yet another loss to Grambling.

Southern’s football program, once the class of the Southwestern Athletic Conference, had gone decades without realizing its potential, gaining a reputation for chewing up coaches and falling short against in rivalry games.

Then, in late 1992, university leadership made a compromise hire. It settled on Pete Richardson — a virtual unknown in Louisiana, a man with a slender build, thick glasses and a quiet, businesslike approach.

“When he first got there, we were looking for a new direction to go in,” said Jabbar Juluke, a safety on the ’93 team and now a high school football coach in New Orleans.

“He had some great ideas. He preached discipline and fundamentals. We bought into it, and we had some talented guys. We just played hard for the guy.”

It showed.

Over the next 17 seasons, Richardson became the face of Southern football, re-establishing the Jaguars as one of the true powerhouses in black college athletics.

From 1993-2007, he won five SWAC championships and four black college national championships — and perhaps most importantly, with 12 wins against Grambling in the Bayou Classic, Richardson cemented his reputation as a big-game coach.

And the Jaguar Nation loved him for it.

“When I came in, I knew I had to change the culture of the football program,” he said. “My main concern was to get some quality people around me. Then we had to get the athletes to believe in themselves and be successful.”

He did plenty of that.

Richardson came to Southern after the 1992 season, after then-athletic director Marino Casem spent one year as interim coach while searching for a permanent replacement.

Casem wanted another former SWAC legend, former Mississippi Valley coach Archie Cooley, to take over. The Southern board of supervisors shot that down, as well as a move to keep Casem in place for another year.

Eventually, spurred by Casem and then-president Delores Spikes, the board settled on Richardson — in part because no one could really argue against him.

A soft-spoken, gentlemanly native of Youngstown, Ohio, Richardson played three seasons with the Buffalo Bills before he got into coaching, rising from high schools to the college level, where he won three conference championships in five years at Winston-Salem State, then a Division II school.

At Southern, Richardson took over a program that had underachieved in the last quarter-century compared to its earlier glory.

Over a 36-year period from 1936-61, the Jaguars had won 11 SWAC titles under Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame member A.W. “Ace” Mumford, for whom their stadium is now named.

But Southern went through 10 coaches after Mumford died in 1962, winning only two conference championships along the way, in ’66 and ’75.

Then came Richardson.

He succeeded right away.

Preaching discipline and fundamentals, Richardson told his players to believe that a sound defense would eventually force opposing offenses into drive-killing mistakes. Southern’s offense, with a straightforward attack, would take it from there.

Richardson also worked his players hard — but they soon learned that all those extra drills were paying off.

His first team at SU went undefeated in conference play and 11-1 overall.

“The main thing was, you had to get the attitudes changed,” Richardson said. “They had some athletes on that team. You had to develop that confidence, get the guys to play hard for 60 minutes and believe in each other.”

The ’93 team gave Richardson his first of four 11-win seasons during the 1990s.

The Jaguars won the black college national title in 1995, defeating nonconference rival Florida A&M in the Heritage Bowl.

From 1997-99, they went undefeated in SWAC play, winning three straight conference crowns. It was the first time Southern won consecutive championships since 1959-60.

All the while, the bandwagon filled up.

In ’99, Southern faced Jackson State in two epic games that essentially determined which school could call itself the team of the ’90s. For the regular-season meeting, fans packed the stands at Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium, some of them even spilling into the aisles. The crowd, more than 62,000 strong, watched Southern get the best of JSU, 26-14.

Two months later, in a rematch at the SWAC championship game, Southern gave Richardson his third straight title before a crowd of before 47,621 fans at Legion Field in Birmingham, Ala.

Big crowds were virtually assured.

When the team hit the road, Southern’s fans, collectively known as the Jaguar Nation, often took over opposing stadiums, flooding the seats with blue and gold — even in far-flung cities like Chicago, Atlanta and Las Vegas.

Perhaps most importantly, however, was the annual big game in New Orleans — the Bayou Classic.

When Richardson took over, Southern had defeated Grambling only five times since the Classic began in 1974 at old Tulane Stadium.

Then, from 1993-2000, the Jaguars won eight consecutive Bayou Classics.

Richardson, in fact, holds the unique distinction of being the only SWAC coach who never lost to Grambling’s Eddie Robinson. He defeated the American icon five straight times before Robinson retired after the ’97 season.

As the years moved on, Richardson changed his style to fit the personnel on hand. When he began at Southern, his offenses were basic and old-fashioned, utilizing the I-formation and Wing-T.

As the years moved on and run-blocking linemen grew scarce, his offenses utilized misdirection, options and four-receiver sets.

And the Jaguars kept winning.

SU claimed its fifth SWAC championship and fourth black college national title under Richardson in 2003, finishing with a 12-1 record.

After that, however, the program underwent several changes.

SU’s administration had moved the coaching staff into Jesse Owens Hall, a worn-down, dirty facility that smelled of mildew and scared away dozens of recruits.

Other programs within the SWAC — including Prairie View and Texas Southern, two sleeping giants in the Houston area, where the Jaguars recruited heavily — began to increase their commitment to football, creating more competition.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina greatly affected — and, in some cases, closed down — some of Southern’s pipeline high schools.

The NCAA also developed its Academic Progress Rate, which forced Southern to take fewer chances on talented athletes with borderline grades.

From 2004-09, the Jaguars posted an overall record of 37-28.

Their final season under Richardson ended with a thud.

Southern looked overmatched and uninterested in a 31-13 loss to Grambling at the Bayou Classic, its fourth loss to the archrival Tigers in six years.

A week later, the Jaguars blew a fourth-quarter lead and lost 30-25 to Texas Southern, finishing 6-5 and fourth in the SWAC Western Division.

Richardson had one year remaining on his contract, but the Southern administration wanted to move on. Essentially, they agreed to get a divorce — although Richardson wanted to keep coaching.

“The decision they made was that they wanted different direction, and that was fine,” he said. “I had to respect that.”

Richardson’s firing was a difficult end to an era that was otherwise successful, and, at times, quietly colorful.

Known as a man of few words, Richardson often drove a hard bargain at practice, and especially during games.

During games, the coach was often known to scream in a high-pitched voice, threatening to fire coaches mid-game, or pull players’ scholarships (he rarely did either).

He also joked on rare occasions, even about himself. Richardson once told wideout Curry Allen — more than 40 years his junior — that Allen didn’t want any piece of the coach, who claimed he “can still bring it.”

More often, however, Richardson said he took his greatest joy in seeing players succeed — in football, in school, in society.

“All I can say is that he’s made a man out of a lot of guys,” said quarterback Eric Randall, who played under Richardson from 1993-95.

“He showed us the importance of what academics could do for us when it came to life after football.”

Richardson, too, has come to terms with life after football.

When Southern parted ways with him in 2009, Richardson, then 63, believed he’d get another chance to do what he’d done for 30-plus years.

“I thought that there would be some opportunities to coach, but there weren’t,” said Richardson, who still lives in Baton Rouge with his wife, Lillian.

“So you never know. We’ll see what happens. Right now, I’m just taking it easy, enjoying life.”

This spring, Richardson said that when his coaching career began, he certainly had goals. They didn’t include making the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame.

“I try to tell people that going into the coaching profession, there’s certain things you want to achieve. You wanted to do positive things for young men, and be a positive influence in their lives,” Richardson said.

“But it’s a great honor to be in there. It shows the respect people have towards you. To be alongside some of the greatest who have ever come through here, it’s a tremendous honor for an individual to have.”